The prostate is a male sex gland that is located between the bladder and the rectum. Prostate cancer occurs commonly in older men. Prostate cancer is typically a disease of aging. It may persist undetected for many years without causing symptoms. In fact, most men die with prostate cancer not from prostate cancer. Approximately 20% of men will develop prostate cancer during their lifetime, yet only 3% will actually die of the disease.

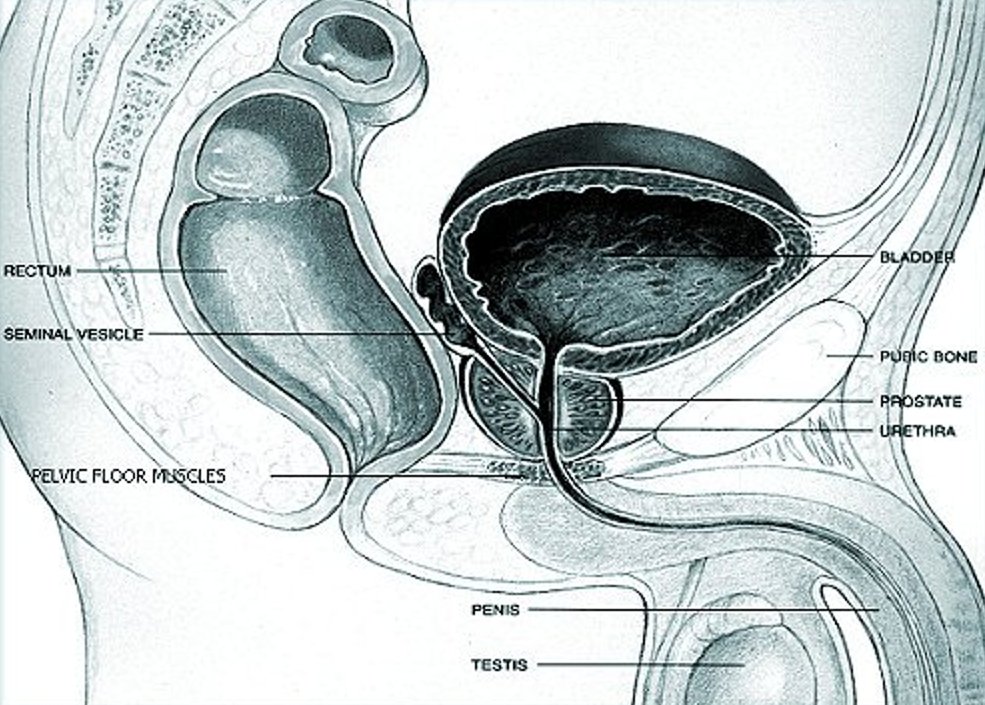

What and where is my prostate?

The prostate is a gland in the male reproductive system located just below the bladder and in front of the rectum. It is about the size of a walnut and is located in the pelvis, at the exit of the bladder, and surrounds the tube known as the urethra (through which urine flows from the bladder to the outside of the body).

Why do we have a prostate?

The prostate gland manufactures an important liquefying component of semen. Sperm are produced in the testicles then stored in the seminal vesicles in a jelly-like substance. At the time of orgasm, the prostate and seminal vesicles contract, mixing their respective contents. The fluid in the prostate contains large amounts of the substance we know as prostate-specific antigen (PSA), which liquefies the sperm mixture, allowing the sperm to move freely in search of an ovum to fertilise.

Understanding Prostate cancer

Cancer begins in cells, the building blocks that make up tissues. Tissues make up the organs of the body.

Normally, cells grow and divide to form new cells as the body needs them. When cells grow old, they die, and new cells take their place.

Sometimes this orderly process goes wrong. New cells form when the body does not need them, and old cells do not die when they should. These extra cells can form a mass of tissue called a growth or tumour.

Tumours can be benign( non cancerous) or malignant ( cancerous)

Prostate cancer occurs when the cells in the prostate gland grow out of control. When cells grow out of control, they initially spread within the prostate and then grow through the capsule that covers the prostate into neighbouring organs, or break away and spread through the bloodstream and lymphatic system to other parts of the body.

Prostate cancer can be relatively harmless or extremely aggressive. Some prostate cancers are slow growing, causing few clinical symptoms. In these cases, a patient will often die with prostate cancer rather than from prostate cancer. Aggressive cancers spread rapidly to the lymph nodes, other organs and especially, bone.

Risk factors for Prostate cancer

The chance of an individual developing cancer depends on both genetic and non-genetic factors. A genetic factor is an inherited, unchangeable trait, while a non-genetic factor is a variable in a person’s environment, which can often be changed.

Non-genetic factors may include diet, exercise, or exposure to other substances present in our surroundings. These non-genetic factors are often referred to as environmental factors. Some non-genetic factors play a role in facilitating the process of healthy cells turning cancerous (i.e. the correlation between smoking and lung cancer).

Other cancers have no known environmental correlation but are known to have a genetic predisposition. A genetic predisposition means that a person may be at higher risk for a certain cancer if a family member has that type of cancer.

Heredity or Genetic Factors

Researchers have estimated that approximately 9% of prostate cancers may be the result of heritable susceptibility genes. Approximately 15% of men with prostate cancer have a first-degree male relative (father or brother) with prostate cancer, compared with 8% of the general population.

Researchers have found that there are 4 alterations or mutations of the Hereditary Prostate Cancer 2 (HPC2) gene. These place men at an increased risk of developing prostate cancer. Two of these alterations result in a 5 to 10 times higher risk of prostate cancer, while the other two result in1.5 to 3 times higher risk of prostate cancer.

Environmental or Non-Genetic Factors

Researchers are unsure why one man will develop prostate cancer and another will not. Interestingly, when people from areas with low prostate cancer rates move to areas with higher prostate cancer rates, they assume the rates of their new environment, although their genetic make-up clearly has not changed. This suggests that environmental factors may play a larger role than genetic factors in the development of prostate cancer.

Age: The incidence of prostate cancer increases dramatically with increasing age. It is unusual for prostate cancer to occur in men under the age of 50. Prostate cancer is most common in men over the age of 55, with the average age at diagnosis being 70. The risk of prostate cancer increases exponentially after age 50. In fact, by the age of 60, as many 34% of men show early evidence of prostate cancer, whereas 70% of men in their 80s have the disease.

Diet: There is increasing evidence that diet plays a role in the development of prostate cancer. Some studies indicate that prostate cancer is more prevalent in populations that consume a diet high in animal fat and/or lacking certain nutrients. Many studies indicate that a higher dietary fat intake is related to a higher risk for prostate cancer. In Asian countries where more fish, vegetables, and soy products are eaten, the incidence and death rate from prostate cancer is less than in Western countries.

Lycopenes (antioxidants in tomatoes, pink grape fruit, watermelon); vitamin E (green leafy vegetables and whole grains); selenium (seafood and whole grain); broccoli,may play a role in preventing, or at least slowing the development of prostate cancer.

Hormones: Some research indicates that high testosterone levels may increase the risk of prostate cancer.

Race: Prostate cancer rates are highest among blacks, intermediate among whites and lowest among native Japanese and Native Americans. Black men are nearly twice as likely to develop prostate cancer as white men and are twice as likely to die from the disease.

Factors not likely to present risk: there have been many attempts to link the following with prostate cancer, but there has been little evidence to support this.

- vasectomy

- sexual activity ,viruses

- sexually transmitted disease.

Prevention

Certain lifestyle modifications may reduce prostate cancer risk. Two-thirds of all cancer deaths in the U.S.A can be linked to tobacco use, poor diet, obesity, and lack of exercise. All of these factors can be modified. Nevertheless, an awareness of the opportunity to prevent cancer through changes in lifestyle is still under-appreciated.

Signs and symptoms

Prostate cancer usually doesn’t produce any noticeable symptoms in its early stages, so many cases of prostate cancer aren’t detected until the cancer has spread beyond the prostate. For most men, prostate cancer is first detected during a routine screening such as a prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test or a digital rectal exam (DRE).

When signs and symptoms do occur, they depend on how advanced the cancer is and how far the cancer has spread.

Less than 5 percent of cases of prostate cancer have urinary problems as the initial symptom. These problems are caused when the prostate tumour presses on the bladder or on the tube that carries urine from the bladder (urethra). However, urinary symptoms are much more commonly caused by benign prostate problems, such as an enlarged prostate (benign prostatic hyperplasia) or prostate infections.

When urinary signs and symptoms do occur, they can include:

- Trouble urinating

- Starting and stopping while urinating

- Decreased force in the stream of urine

Cancer in the prostate or the area around the prostate can cause:

- Blood in the urine

- Blood in the semen

Prostate cancer that has spread to the lymph nodes in the pelvis may cause:

- Swelling in the legs

- Discomfort in the pelvic area

Advanced prostate cancer that has spread to thebones can cause:

- Bone pain that doesn’t go away

- Bone fractures

- Compression of the spine

Screening and Early Detection

While with most cancers, early detection increases the chance of a cure; it is unclear whether screening for prostate cancer reduces the number of deaths from this disease. Despite the controversy, it is still recommended that men undergo annual screening for this disease utilizing digital rectal examination (DRE) and PSA blood test .Currently, it is recommended that men begin annual screening with PSA and DRE at age 50 and that men from Afro Caribbean origin and men with a strong family history of prostate cancer begin annual screening at age 40-45yrs.

The combination of detail gained by the PSA ,DRE and scanning improves the chance of identifying prostate cancer at an early stage.

- Digital Rectal Exam (DRE): During a digital rectal exam (DRE), a physician inserts a gloved finger into the rectum to assess the texture and size of the prostate. If there are any abnormalities in the texture, shape or size of the gland further investigation might be necessary.

- PSA Blood Test: A simple blood test allows laboratory technicians to determine PSA levels. PSA is a protein that is normally secreted and disposed of by the prostate gland. Its function is involved in liquefying sperm.

It’s normal for a small amount of PSA to enter the bloodstream. However, if a higher than normal level is found, it may be an indication of prostate infection, inflammation, benign prostate enlargement, or cancer. It can also be higher within 72 hours of ejaculation. In patients with a known diagnosis of prostate cancer, the PSA level roughly reflects the total amount of cancer. The higher the PSA level , the more likely that the cancer is advanced. - Transrectal Ultrasonography: During transrectal ultrasonography, a small probe is inserted into the rectum. The probe emits high frequency sound waves that bounce off the prostate and produce echoes. A computer uses these echoes to create a picture called a sonogram. It is mainly helpful in determining the size of the prostate which in turn helps work out if the PSA is appropriate for that size (PSA Density ) .

- Multi Parametric MRI Scanning

Multi-parametric magnetic resonance imaging (mpMRI) works by creating detailed

images of the prostate that enable clinicians to better detect suspected prostate

cancer. If suspicious areas are seen they can then be targeted during biopsy.

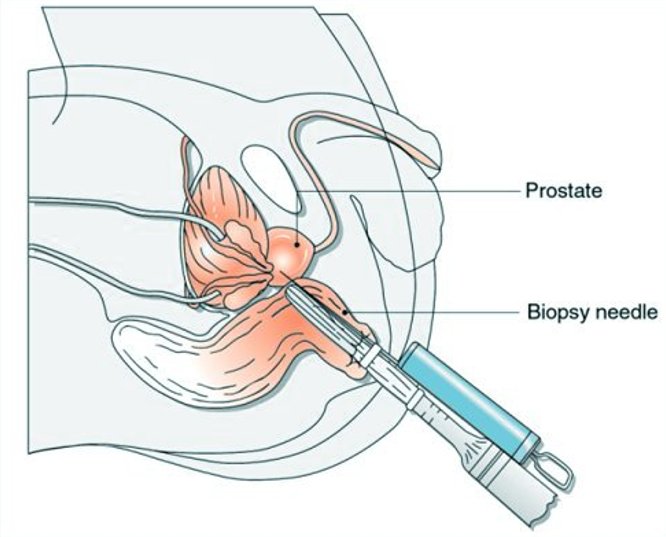

- Prostate biopsy:

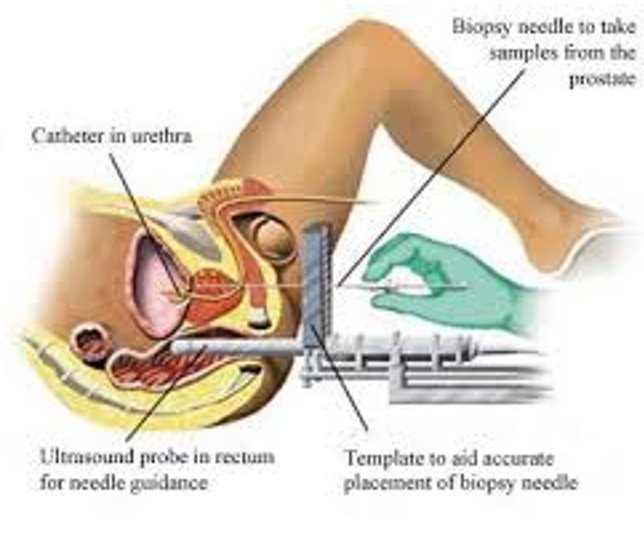

The standard procedure is by Transperineal template biopsy of the prostate. This involves using a grid (or template) to insert several fine needles through the skin in the area between the scrotum and the anus (the perineum) into the prostate gland in order to obtain several tissue samples for testing. It can be done under light general or local anaesthetic as a day case. I favour the former, as it is more comfortable for the patient.

- In the past transrectal biopsy was commonly used. An ultrasound probe is inserted into the rectum to guide the biopsy needle. It is associated with a higher level of urinary infection and sepsis as the needle is passed through the rectum. Guided by images from the probe, a fine, spring-propelled needle retrieves several very thin sections of tissue from the prostate gland. This is done under local anaesthetic. It is still used when only a a small amount of tissue is needed to confirm the diagnosis.

A pathologist who specializes in diagnosing cancer and other tissue abnormalities evaluates the samples. From those, the pathologist can tell if the tissue removed is cancerous and estimate how aggressive the cancer is.

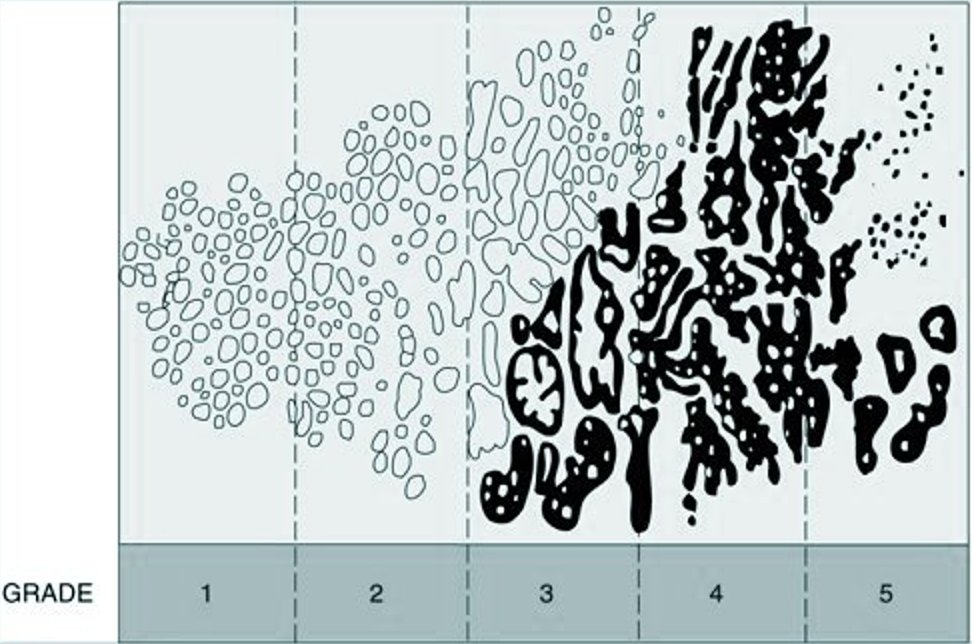

Cancer that is removed by surgical resection or needle biopsy will be classified according to the Gleason Grading System for prostate cancer. This grading system, on a scale of 2-10, helps physicians predict how rapidly the cancer is likely to spread. The tissue samples are studied, and the cancer cells are compared with healthy prostate cells. The more the cancer cells differ from the healthy cells, the more aggressive the cancer and the more likely it is to spread quickly.

The pathologist identifies the two most aggressive types of cancer cells when assigning a grade. The most common scale used to evaluate prostate cancer cells is called a Gleason score. Based on the microscopic appearance of cells, individual ratings from 1 to 5 are assigned to the two most common cancer patterns identified. These two numbers are then added together to determine your overall score. Scoring can range from 2 (nonaggressive cancer) to 10 (very aggressive cancer).

Generally, higher Gleason scores are associated with more advanced and more rapidly growing cancers than lower scores.

Determining how far the cancer has spread

Once a cancer diagnosis has been made, further tests to help determine if or how far the cancer has spread can be done.Many men don’t require additional studies and can directly proceed with treatment based on the characteristics of their tumours and the results of their pre-biopsy PSA tests.

- Bone scan. A bone scan takes a picture of the skeleton in order to determine whether cancer has spread to the bone. Prostate cancer can spread to any bones in the body, not just those closest to the prostate, such as the pelvis or lower spine.

- Ultrasound. Ultrasound not only can help indicate if cancer is present, but also may reveal whether the disease has spread to nearby tissues.

- Computerized tomography (CT) scans. A CT scan produces cross-sectional images of the body. CT scans can identify enlarged lymph nodes or abnormalities in other organs, but they can’t determine whether these problems are due to cancer. Therefore, CT scans are most useful when combined with other tests.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). This type of imaging produces detailed, cross-sectional images of your body using magnets and radio waves. An MRI can help detect evidence of the possible spread of cancer to lymph nodes and bones.

- PSMA PET Scan Prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) imaging is a nuclear medicine exam using positron emission tomography (PET) to detect prostate cancer. PSMA PET is very sensitive for detecting prostate cancer, with accumulating evidence suggesting it is superior to conventional imaging tests such as CT scans or bone scans. It is particularly helpful in determining if prostate cancer has spread beyond the prostate into lymph nodes, other soft tissues and bones.

- Lymph node biopsy. If enlarged lymph nodes are found by a CT scan or an MRI, a lymph node biopsy can determine whether cancer has spread to nearby lymph nodes. During the procedure, some of the nodes near the prostate are removed and examined under a microscope to determine if cancerous cells are present.

Prostate cancer staging

All the information gained from the various diagnostic tests help categorize and work out the extent of the cancer. This is called staging.

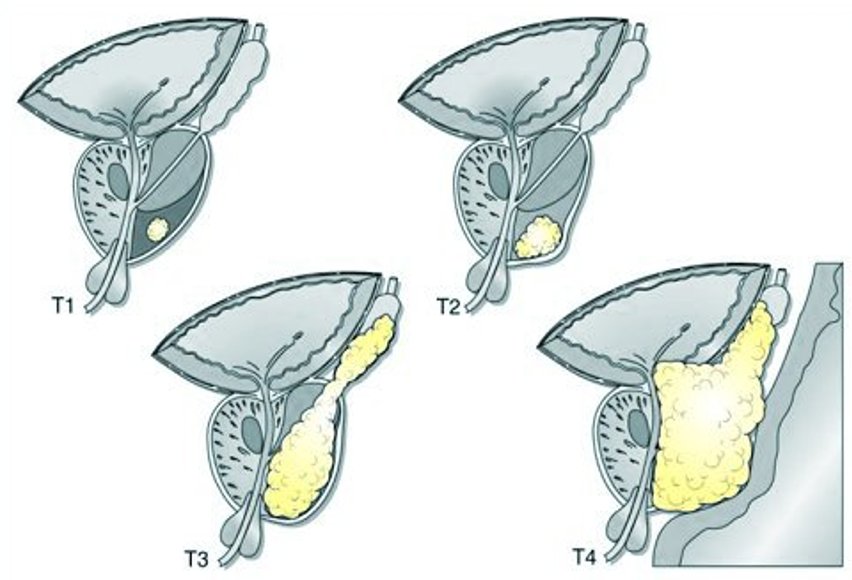

Prostate cancer is staged with the TNM system based on the American Joint Committee on cancer ( AJCC):

T: information about the primary tumour

N: information about lymphnodes

M: information about distant metastases.

T1: The doctor cannot feel the tumour or detect it with imaging such as trans rectal ultrasound.

T1a: The tumour is found when the prostate tissue is taken during a trans urethral resection of the prostate. The tumour involves 5% or less of the prostate sample.

T1b: The tumour is found when the prostate tissue is taken during a trans urethral resection of the prostate. The tumor involves more than 5% of the prostate sample.

T1c: The tumour is found by needle biopsy done because of a raised PSA.

T2: The doctor can feel the tumour but it is confined within the prostate.

T2a: The tumour involves half or less of only one side( left or right) of your prostate.

T2b: The tumour involves half or more of one side of your prostate

T2c: The tumour involves both sides (lobes) of the prostate.

T3: The cancer extends outside the surrounding border (capsule) of the prostate and may involve the seminal vesicle

T3a: The tumour has extended outside of the prostate on one side.

T3b: The tumour has extended outside of the prostate on both sides.

T3c: The tumour has invaded one or both of the seminal vesicles

T4: The tumour has invaded other nearby organs, including part of the bladder, the sphincter, or the rectum.

N0: The cancer has not spread to any lymphnodes.

N1: Cancer has spread (metastasis) to one or more nearby lymphnodes in the pelvis.

M0: the cancer has not spread beyond the regional lymphnodes.

M1: the cancer has spread beyond the regional lymphnodes

M1a: the cancer has spread to distant (outside the pelvis) lymphnodes

M1b: the cancer has spread to the bones

M1c: the cancer has spread to the other organs – lungs, liver, brain, with or without bone metastases.